Crimea will cost Russia at least $ 400 bn this year

The West is threatening further sanctions should Russia proceed with the formal annexation of Crimea. There is no need. The crisis has already cost Russia $187bn so far and almost certainly wrecked any chance of economic growth this year. And the impact of the crisis could do roughly $440bn worth of damage over the whole year — and that is before the West inflicts a single cent’s worth of sanctions, according to bne’s (very rough) estimates.

.jpg)

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s decision to send in the army to Crimea is a massive own goal as far as Russia’s economy is concerned. This was the year Russia was supposed to emerge from the aftermath of the 2008 crisis and grow by up to 3.5%. However, it was obvious even before the first squaddie climbed into a truck that intervening in Ukraine militarily was going to not only cost a lot of money, but also do enormous economic damage to the already fragile investment climate.

«Regardless of the West’s response to the Crimean crisis, the economic damage to Russia will be vast. First, there are the direct costs of military operations and of supporting the Crimean regime and its woefully inefficient economy (which has been heavily subsidized by Ukraine’s government for years),» exiled Russian economist Sergei Guriev said in a recent article.

In this piece, bne attempts to tot up some of the costs already incurred by the Crimean crisis and guestimate costs that will be incurred over the rest of the year. While a lot of the estimates are wide open to debate, it is still clear that Russia has inflicted more economic damage on itself than the West could ever hope to achieve with Iran-style punitive sanctions.

The cost so far

As Russian troops appeared on the streets of eastern Europe’s favourite holiday resort in February, Russia’s stock market tanked, losing 15% in a day and wiping an estimated $55bn off the market capitalization at the shaky stroke of a pen. While most pundits were expecting Russia to cancel its $15bn bailout deal for Ukraine and possibly some economic retaliation after the Maidan government took over in Kyiv, no one was expecting the display of force.

Running total: $55bn

Equity investors were already unsettled by emerging market uncertainties, with $130m leaving in the week before the Crimean crisis alone, according to Emerging Market Value Portfolio. But redemptions have probably since accelerated: Let’s call it a round $1bn for the whole year to date of redemptions from funds.

Running total: $56bn

The same collywobbles will also have accelerated capital flight, which the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) was hoping would slow this year. An estimated $17bn left the country in January according to the authorities — the same amount as that month a year ago — but Renaissance Capital’s chief economist, Charles Robinson, estimates $50bn has already left in the first quarter of this year.

Running total: $106bn

The side effect of capital flight is to continue to push the ruble’s value down, which fell 10% on the start of hostilities. Russians were already beginning to panic in December as the ruble has been under pressure for months. The population were converting rubles to dollars at a record pace in December — about $2bn a month, or a total of $6bn since the New Year, but that too accelerated in March: the CBR was forced to spend $11bn on trying to prop the ruble up in the last month.

Running total: $117bn

And the loss of this money to the economy was before Russia spent a penny on actually running its military campaign, currently estimated to have cost $50bn-70bn — more than it cost to put the Sochi Olympics on. With an estimated 60,000 Russian soldiers massed on the Ukrainian border, that number is climbing daily.

Running total: $187bn

Rest of this year

That bill is only the tip of the iceberg. Even if a deal with the EU and Maidan government were signed today, the costs from the shock Putin has given the West is going to reverberate all year, if not longer.

The most obvious direct cost to the Kremlin of taking over Crimea is Russia is going to have to pay to keep the region going. The Kremlin has already sent a reported $440m in cash to tide Crimea over, but an article in Vedomosti put the annual cost of subsidies, pension payments etc. at $3bn a year.

Putin is well aware of the cost of taking on crappy regions: after taking over Abkhazia, a breakaway region of Georgia, Russian grants now make up 70% of the region’s budget for several years — and half of that was stolen by the local elites, according to reports. Crimea is unlikely to be different.

Running total: $190bn

However, the cost of running Crimea is the least of the Kremlin’s worries. Once the dust literally settles, attention will inevitably turn to the dire state of Ukraine’s economy: the country is bankrupt and on the verge of collapse. It needs billions of dollars of aid keep it running.

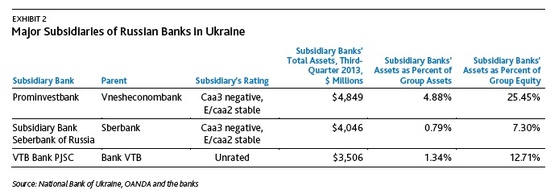

Some of Russia’s largest banks are exposed to Ukrainian risk directly and via their subsidiaries to the tune of $30bn, according to estimates by Moody’s Investors Service. More than half of these exposures ($17.4bn) are via subsidiaries of Russian banks and some or all of this could be lost if the banking sector collapses. Indeed, if the EU “takes” Ukraine, it is not unlikely that Russia will precipitate a collapse on purpose.

Running total: $223bn

Almost as much money that left Russia in all of last year ($63bn) had already fled by the end of March and the CBR spent a total $30bn in 2013 defending the currency. This year capital flight is expected to soar to $130bn, says Goldman Sachs, which means the CBR will probably have to double its interventions to some $60bn to keep some sort of currency stability.

«The Achilles heel of the Russian economy remains the flow abroad of Russian capital following any shock. We would also think that any sanctions or even the threat of sanctions will be ultimately targeted at these flows,» Goldman said in a note.

Running total: $283bn

Capital flight will only pull the weakening ruble down further, which in turn increases the costs to the budget. The ruble has already fallen by 10% this year, but Renaissance Capital estimates that a further fall in the ruble’s value this year will add another $10bn to the government’s costs.

Running total: $293bn

The incursion into Crimea was as much a shock to Russia’s business leaders as it was to the politicians in Brussels and Washington, and is bound to hurt domestic investment. Russia desperately needs fixed investment to rise if it is to have any chance of economic growth this year, but investment had already stalled by last year. Now there is talk of war, Russia’s business captains are even less likely to invest than before. Fixed investment into the Russian economy totaled RUB2.33 trillion ($77.76bn) in 2013, but Bank of America Merrill Lynch forecasts that investments in fixed capital will decrease 3.3% as of the end of 2014, or by about $2.33bn.

Running total: $295bn

Russia attracted a whopping $94bn of foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2013, making Russia the third largest recipient of FDI in the world, according to a February ranking by the UNCTAD, although a big chunk of that was part of the TNK-BP/Rosneft deal. But if Russian investors are unnerved, can you image how the foreign investors feel? By the middle of March several big deals were already looking shaky.

Again, it is impossible to measure just how many deals-that-might-have-been are now on ice, but some high-profile joint ventures are already in trouble. Swedish car producer Volvo said in March it was taking a second look at a proposed partnership with Russian state-owned railway equipment and tank maker Uralvagonzavod (UVZ) to make modern armored cars due to the situation in Ukraine, worth about $100m

Separately, state-owned oil major Rosneft signed a binding deal to sell its oil-trading arm to Morgan Stanley in December for hundreds of millions of dollars. That deal is now in doubt and may be nixed by the US Foreign Investments Committee.

Assuming a modest 20% contraction in FDI against last year, that would wipe out another $19bn of money lost to the economy.

«A significant decline in FDI — which brings not only money but also modern technology and managerial skills — would hit Russia’s long-term economic growth hard. And denying Russian banks and firms access to the US (and possibly European) banking system — the harshest sanction applied to Iran — would have a devastating impact,» says Guriev.

Running total: $314bn

The stock market has already been hit, but it could be hit again if its performance in recent years is anything to go by: the RTS index was down by 72.4% in 2008, 21.9% in 2011 and 6.8% in 2013 on crisis-related fears. Predictions for this year’s gains were already modest, but there is a very real chance that Russian stocks will return a loss instead. Assuming a modest 5% year-on-year fall for the full year, that would destroy another $50bn of market capitalization.

Running total: $364bn

Even if the market remains flat, collateral damage could be a string of IPOs that were on the docket, but are now almost certainly going to be cancelled. Regional shoe retailer Obuv Rossii has already postponed its $55m IPO until the second half of the year (if then) due to the brouhaha. And the IPO plans of much larger companies are in doubt: retailer Lenta, childrens’ store Detski Mir, German wholesaler Metro and retail bank Credit Bank of Moscow were all also hoping to get IPOs away this year (and raise $1bn, $440m, €1.7bn and $500m respectively), collectively worth $4bn.

Running total: $368bn

And those are just the privately owned companies with listing aspirations; the state was hoping to restart its long-delayed privatization programme in the second half of this year, after an IPO window opened briefly in the second half of last year. Fat chance that foreign investors will fork out billions of dollars for shares in state-owned enterprises now. Given state-owned Sberbank raised just over $5bn last year with a secondary public offering, pencil in the same this year for the non-privatization programme.

Running total: $373bn

The bogeyman of financial sanctions has been raised as a possible punitive reaction by the West against Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, but actually it is highly unlikely because western banks are so heavily exposed to Russia: according to Bank of International Settlements (BIS) data, European banks have $193.8bn in exposure to Russia, US banks $35.2bn, Japan $17.2bn, Switzerland $8bn, and South Korea $5.2bn. If the West tries to freeze Russian assets abroad, Russia could easily retaliate by refusing to pay these debts back.

Likewise, oil and gas majors Rosneft and Gazprom owe a combined $90bn in debt and bonds with four state banks Sberbank, VTB, VEB, Rosselkhozbank owing another $60bn in foreign credits. A Kremlin aide has already warned that if financial sanctions are imposed on Russia, these institutions might refuse to pay their loans off.

But where Russia will be hurt, even without sanctions, is with bond issues. Russia’s sovereign external debt is very modest indeed, but its external commercial debt has soared in recent years (although the maturities now are a lot longer than they were in 2008): Russia’s total external debt rose to $732bn as of January 1, 2014, from $636bn a year earlier and $464bn at the start of 2008, according to the CBR, with the bulk of new debt raised by Russian state companies.

Although state-owned Gazprom Neft got a $2.5bn syndicated loan deal away in the middle of March, largely financed by a club of European and US banks, plans by another 10 big Russian companies to raise $8bn in loans this month are reportedly in difficulty now.

Running total: $396bn

At the same time, the cost of these bonds has already increased significantly. Last year saw a boom in Russian bond issues when yields fell to about the 4% for state and quasi-state issues, but the rates have more-or-less doubled on the government’s OFZ in recent months, which broke through 9% earlier this month.

Again it is very hard to guess the value of bonds-that-might-have-been. But given Russian corporates were adding approximately $60bn of debt a year over the last five years, and again assuming a modest 20% reduction in bond issues, the value of bonds that won’t be issued will be on the order of $12bn.

Likewise, making a guestimate of the extra cost this borrowing will come in at due to the rise in yields caused by the crisis could add at least another $3bn.

Running total: $411bn

The spillover from the crisis is also going to hurt the banking sector and cost it money in the form of the need for higher capital and an increase in bad debt. According to bankers in Moscow, corporate non-performing loans are already rising and lending will slow even further: Fitch says that Tier 1 capital could be reduced by up to 2%, which would be worth $12bn.

Running total: $423bn

Bad loan levels were already accelerating on the back of the economic slowdown, but that problem will get even worse now.

«In light of the potential economic slowdown, we expect nonperforming loans (NPLs) in the system to increase. Our base-case forecast estimates a system-wide NPL ratio of 8.0%-8.5% this year, and could go higher if the current volatility persists,» says Moody’s.

The National Collection Service estimates total bad loans have reached about RUB435bn ($12.8bn). And if this only increases by the same 40% that it grew last year, it will be another $5bn lost to the economy.

Running total: $428bn

Corporate loans will also be affected. «There is a risk that the currency devaluation will exacerbate negative asset quality trends in foreign currency loans, which we estimate constitute around 17% of the total loan book and are mainly concentrated in corporates. Approximately 50% of these loans are to borrowers that do not have matching foreign currency cash flows and they would need to absorb the increased repayment burden caused by the ruble depreciation,» Moody’s said in a report, without putting any actual numbers on the cost. Let’s call it another $5bn.

Running total: $433bn

Ironically, trade is probably one area that will be least affected. Indeed, it is the heavy trade flow between Russia and Europe that makes the European powers like Germany so reluctant to slap sanctions on Russia. About half of Russia’s exports go to Europe, but only 3% to the US. Conversely, only 7% of Europe’s exports go to Russia (and next to no US exports). But in money terms, the EU exports more to Russia ($264bn) than Russia to the EU ($152bn). The upshot is trade sanctions can be ruled out because Russia carries a very big stick in any trade war.

Whatever happens next, the crisis has already ruined Russia’s chances for economic recovery this year. Last year Russia put in a very disappointing 1.4% growth but analysts were hoping this year would be better, predicting between 2% and 3.5% growth for the full year. The recovery that should have come last year would arrive this year. Not any more. Goldman Sachs, among many, downgraded Russia’s growth outlook to 1% at best on March 14. Other analysts are speculating the economy may even contract this year. A 0.5% contraction would destroy another $10bn of value.

Running total: $443bn

Source: Business New Europe.

Translation: MediaPort™

Illustration: Hendrick Goltzius (1588)